Abstract

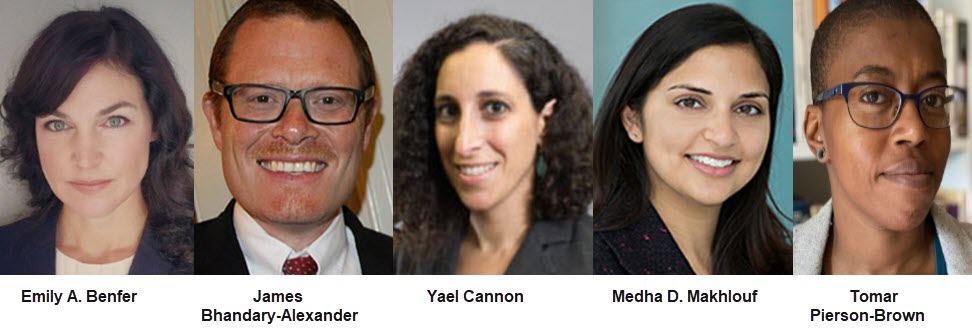

Excerpted From: Emily A. Benfer, James Bhandary-Alexander, Yael Cannon, Medha D. Makhlouf, and Tomar Pierson-Brown, Setting the Health Justice Agenda: Addressing Health Inequity & Injustice in the Post-pandemic Clinic, 28 Clinical Law Review 45 (Fall, 2021) (150 Footnotes) (Full Document)

One of the goals of clinical legal pedagogy is to teach students about the lawyer's role in ensuring both access to, and the quality of, justice for low-income and historically marginalized populations. The COVID-19 pandemic illustrated how--for far too many--justice is inaccessible, inequity is rapidly increasing, and health justice is out of reach. Historically marginalized groups and low-income populations experienced disproportionate infection and mortality rates from COVID-19, as well as the highest rates of unemployment, barriers to health care access, food insecurity, and extreme eviction risk during the pandemic. These disparities stem from the social determinants of health (SDOH). SDOH “encompass[ ] the full set of social conditions in which people live and work,” and drive health inequity for people living in poverty, people of color, and other historically marginalized groups. Structural determinants of health, including the political and legal systems in which discrimination can become embedded, influence poor health outcomes. It is upon the legal profession to uncover how the law, laden with bias and discrimination, can operate as a vehicle of subordination, creating barriers to opportunity, long-term hardship, and poor health. No other profession bears more responsibility for the role of law in lifting or oppressing members of society. The pandemic-related increase in the need for legal services highlighted the urgency of not only providing the next generation of lawyers with foundational lawyering skills, but also imbuing them with a sense of legal stewardship. In this way, the pandemic underscored the need for clinical legal education to adopt strategies that both increase lawyering skills and directly address the structural determinants at the root of the justice crisis.

One of the goals of clinical legal pedagogy is to teach students about the lawyer's role in ensuring both access to, and the quality of, justice for low-income and historically marginalized populations. The COVID-19 pandemic illustrated how--for far too many--justice is inaccessible, inequity is rapidly increasing, and health justice is out of reach. Historically marginalized groups and low-income populations experienced disproportionate infection and mortality rates from COVID-19, as well as the highest rates of unemployment, barriers to health care access, food insecurity, and extreme eviction risk during the pandemic. These disparities stem from the social determinants of health (SDOH). SDOH “encompass[ ] the full set of social conditions in which people live and work,” and drive health inequity for people living in poverty, people of color, and other historically marginalized groups. Structural determinants of health, including the political and legal systems in which discrimination can become embedded, influence poor health outcomes. It is upon the legal profession to uncover how the law, laden with bias and discrimination, can operate as a vehicle of subordination, creating barriers to opportunity, long-term hardship, and poor health. No other profession bears more responsibility for the role of law in lifting or oppressing members of society. The pandemic-related increase in the need for legal services highlighted the urgency of not only providing the next generation of lawyers with foundational lawyering skills, but also imbuing them with a sense of legal stewardship. In this way, the pandemic underscored the need for clinical legal education to adopt strategies that both increase lawyering skills and directly address the structural determinants at the root of the justice crisis.

Health justice is the eradication of social injustice and health inequity caused by discrimination and poverty. The health justice framework provides a model for training students to recognize the structural and intermediary determinants of health at the root of their clients' hardship, and to actively work with the community to address barriers to health equity and social justice. The framework centers on engaging, elevating, and increasing the power of historically marginalized populations to address structural and systemic barriers to health, as well as to compel the adoption of rights, protections, and supports necessary to the achievement of health justice. In the law clinic setting, health justice offers a holistic, interprofessional, and proactive approach to addressing social injustice. It teaches students to investigate the roots of their clients' legal crises and to identify leverage points to shift the deeply connected health disparities and injustices that plague marginalized communities. A holistic understanding of social injustice and health inequity prepares students to seize those opportunities to develop proactive--rather than reactive--legal interventions to address potential health crises. While we have used the health justice framework to conceptualize and explain the work of medical-legal partnerships (MLPs) in this Article, the framework can be adapted to any law school clinic setting.

This Article arose from a discussion among five law school clinicians and law professors who have over four decades of combined experience designing and working in MLPs to address health-harming legal needs for low-income and historically marginalized patients. The Article provides our reflections on the successes and challenges of the MLP model for promoting health justice during the COVID-19 pandemic. It also memorializes our identification of key principles that, we think, could and should be adopted across all clinics, regardless of subject matter, to advance social justice and health equity and enhance student learning. Part I provides an overview of the relationship between structural injustice and pandemic-related health impacts. It then explains how individual-level responses to these crises have largely failed to protect the populations that are widely considered marginalized in U.S. society. Finally, it describes the role of legal interventions in combatting health inequity. Part II introduces the health justice framework, showing how MLPs have used it to address “wicked problems” at the intersection of law, health, race, and poverty. Part III proposes maxims for law clinics in general to adopt to advance health justice, drawn from the authors' experiences over the past eighteen months.

We believe that the health justice framework and our reflections can be useful to all clinicians because of the relationship between unmet legal needs and poor health: When clinics intervene to help clients address financial or food insecurity, unstable or unsafe housing, employment discrimination, inadequate educational supports, immigration issues, and interpersonal or community violence, criminal justice issues, among other legal needs, we address health justice. Because we are all, ultimately, affecting the SDOH and the structures that direct health outcomes, this framework provides helpful insights to clinicians working across a range of legal issues. Amid the global COVID-19 pandemic, the link between health equity and access to justice is clearer and more salient than ever before.

[. . .]

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated health inequity and racial injustice in a tangible and unmistakable way. Across the country, historically marginalized, subordinated, and exploited people, many of whom were our clinic clients, have suffered job loss, COVID-19 infection and mortality, food and housing insecurity, and barriers to access to justice. Despite experience with past epidemics, which made the heightened risk entirely predictable, few preventive or protective measures were taken and, as a result, racial, health, and economic injustice can be expected to proliferate in the post-pandemic setting. The legal field has a special role to play in preventing this outcome by uncovering how the law operates as a vehicle of subordination, especially in times of crisis, and how it must change. The pandemic highlighted how certain MLP features can aid law school clinics in identifying injustice at the root of poor health, and can act to make law work to improve health for clients and community. However, this requires the legal profession to step up, accept responsibility, and act. Otherwise, we are witting bystanders to the cycle of despair.

In the post-pandemic law school clinic, we must acknowledge the role of law in lifting--or oppressing--members of society, and we must fulfill our obligation to train the next generation of lawyers to recognize the structural and intermediary determinants of health at the root of their clients' hardship. We must actively collaborate with the community and other disciplines to address barriers to health equity and to racial and social justice. This Article drew from the tested strengths of the MLP clinic model to offer maxims of health justice that can be adopted across clinics. At the core of the health justice agenda, we are called to teach our students to engage and elevate the power of our clients and other historically marginalized people, in the effort to address structural and systemic barriers and compel the adoption of rights, protections, and support. Ultimately, we must leverage every opportunity to address social and racial injustice and prepare our students to be stewards of equitable laws and policies focused on the achievement of health justice for all people.

Emily Benfer, Visiting Professor of Law and Public Health, Wake Forest University School of Law and School of Medicine;

James Bhandary-Alexander, Medical-Legal Partnership Legal Director, Clinical Lecturer and Research Scholar, Yale Law School;

Yael Cannon, Associate Professor, Director, Health Justice Alliance Law Clinic, Georgetown University Law Center;

Medha D. Makhlouf, Assistant Professor, Director, Medical-Legal Partnership Clinic, Penn State Dickinson Law;

Tomar Pierson-Brown, Director, Health Law Clinic, Clinical Associate Professor of Law, Associate Dean for Equity and Inclusive Excellence, University of Pittsburgh School of Law.

Emily A. Benfer's contribution to this article occurred prior to her position as a Senior Policy Advisor to the White House and American Rescue Plan Implementation Team and reflects her personal views only.