Become a Patreon!

Abstract

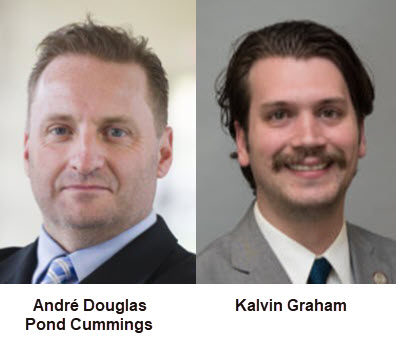

Excerpted From: André Douglas Pond Cummings and Kalvin Graham, Racial Capitalism and Race Massacres: Tulsa's Black Wall Street and Elaine's Sharecroppers, 57 Tulsa Law Review 39 (Winter 2021) (196 Footnotes) (Full Document)

United States history is marked and checkered with grievous race massacres dating back to the end of slavery. These race “riots,” as they are benignly referred to in some quarters, occurred infamously in Tulsa, Elaine, Rosewood, Chicago, Detroit, and so many other lesser remembered cities. The starkest period of race massacres in the United States, including each of those just mentioned, occurred in the early 1900s, between 1919 and 1923 when Black Americans, newly empowered by service in a world war and having gained available land grants in territories where indigenous peoples were forced to abandon, began finding economic and political footholds. When in 1919 and 1921, African American citizens were becoming successful and independent economically, race massacres annihilated these fledgling successes. At a time when economic independence was becoming a light at the end of a long, dark tunnel for Black Americans, white supremacy and racial capitalism worked to ensure that this light and hope was quashed. This quashing of early African American economic success, particularly on Tulsa's Black Wall Street and in the fields of Elaine, Arkansas, sent shock-waves of oppression that still reverberate today.

United States history is marked and checkered with grievous race massacres dating back to the end of slavery. These race “riots,” as they are benignly referred to in some quarters, occurred infamously in Tulsa, Elaine, Rosewood, Chicago, Detroit, and so many other lesser remembered cities. The starkest period of race massacres in the United States, including each of those just mentioned, occurred in the early 1900s, between 1919 and 1923 when Black Americans, newly empowered by service in a world war and having gained available land grants in territories where indigenous peoples were forced to abandon, began finding economic and political footholds. When in 1919 and 1921, African American citizens were becoming successful and independent economically, race massacres annihilated these fledgling successes. At a time when economic independence was becoming a light at the end of a long, dark tunnel for Black Americans, white supremacy and racial capitalism worked to ensure that this light and hope was quashed. This quashing of early African American economic success, particularly on Tulsa's Black Wall Street and in the fields of Elaine, Arkansas, sent shock-waves of oppression that still reverberate today.

This article will examine the role of racial capitalism in the race massacres of Tulsa, Oklahoma in 1921 and Elaine, Arkansas in 1919. This article begins with an introduction to racial capitalism. Next, it describes the race massacres in the Greenwood District of Tulsa and the evisceration of Black Wall Street before examining the race massacre in Elaine and the destruction of the lives and fortunes of Black sharecroppers there. Thereafter, the article describes the role that racial capitalism and the economic exploitation of Black Americans played in carrying out that massive destruction of Black human capital. Finally, the article describes how the echoes of these race massacres continues to sound today in a white supremacist refrain that is quintessentially the song that accompanies the founding and growth of the American economy.

First then, what is racial capitalism and what role has it played in the race massacres that checker U.S. history?

II. Racial Capitalism

Capitalism, much of the world's current economic system, possesses a long, storied and ofttimes sordid history. Indeed, the sixteenth and seventeenth century origin story of capitalism is often clouded and mystified when narrated typically favoring expansive generalizations and superlatives describing “innovation,” “markets,” “invention,” “credit,” “trade,” “money systems,” “interchangeable parts,” “steam power,” and the like. What is often ignored and forgotten historically is the story of the millions of lives that were shattered in service of innovation, markets, invention, trade, interchangeable parts, and the like, as the transition from feudalism to early capitalism literally crushed millions of human beings, most often persons of color, with many of those effects still felt and relevant today.

Scholars of late, in an attempt to colorize the sanitized version of capitalism's history, have taken to referring to this shattering of human life as “racial capitalism.” Racial capitalism cuts through the clouded mystification of capitalism's evolution story by linking it to the origin's most indispensable component: exploitation. Particularly, the human exploitation of those races deemed most exploitable--the non-white. To founding theorist Cedric Robinson, racial capitalism necessarily implicates the fact that “the development, organization, and expansion of capitalist society pursued essentially racial directions” and that “the historical development of world capitalism was influenced in a most fundamental way by the particularistic forces of racism and nationalism.” Further developing Robinson's framework, scholars, and activists today are defining racial capitalism as a “conceptual framework to understand the mutually constitutive nature of racialization and capitalist exploitation, inter alia, on a global scale, in specific localities, in discrete historical moments, in the entrenchment of the carceral state, and in the era of neoliberalization and permanent war.”

Racial capitalism makes manifest that capitalistic success, white owned wealth and property, was built on the backs of those exploited minority populations, including through slavery, involuntary servitude, manifest destiny, and oppression. If racial capitalism involves the process of deriving economic and social value from the racial identity of another, then historian Gerald Horne demonstrates the exploitative utility of this framework when writing that: London was a prime beneficiary of this systemic cruelty .... As scholar William Pettigrew has argued forcefully, the African Slave Trade rested at the heart of what is still held dear in capitalist societies: free trade, anti-monarchism, and a racially sharpened and class-based democracy. Like a seesaw, as London rose Africa and the Americas fell. As one scholar put it, “the industrial revolution in England the cotton plantation in the South were part of the same set of facts.” ... More to the point ... “without English capitalism there probably would have been no capitalis[t] system of any kind.” As early as 1663, an observer in Surinam noticed that “Negroes [are] the strength and sinews of the Western world.” The enslaved, a peculiar form of capital encased in labor, represented simultaneously the barbarism of the emerging capitalism, along with its productive force.

“[T]he barbarism of emerging capitalism” through the “labor” of the “enslaved” complicates the process by which capitalism is recounted and supported. Meticulously whitewashing the exploitation of the African slave trade as well as the oppression of millions and the continuing vestiges of this exploitation and slavery existing today remains a bedrock principle in capitalistic theorizing.

Those that have historically benefited from racial capitalism engage in a common sophistry which embraces historical inaccuracy by ignoring that the wealthy and propertied ascended to places of prominent wealth and power through flagrantly exploiting and oppressing the enslaved and powerless, but rather arrived at this exalted status organically. Stated another way, racial capitalists were often slaveholding figures whose primary business is usurping land from exploited indigenous populations and “working” that land by forced slave labor through exploited African populations. Racial capitalism ignores the historical exploitation of the victimized and concomitantly ignores the role that such exploitation played in the rise to the propertied and wealthy status of the exploiters.

Whitewashed capitalism's casuistry refuses to account for the reality that the very wealth and property that is secured in the hands of the uber wealthy exists primarily because of the exploitation and oppression visited upon the exploited and enslaved. Stated differently, the position of the wealthy and propertied has been bestowed upon him not by nature of his hard work, determination, or good fortune, but rather has come purchased through the slavery, bondage, and oppression of particular races that capitalism itself sprang from. Racial capitalists would have the world believe that the wealthy and propertied arrived at their place purely by virtue of wisdom, hard work, and providence while cynically refusing to acknowledge that those that have been oppressed and exploited by the wealthy and propertied are the very reason that the wealthy garnered those riches. And tragically, some capitalists suggest that the oppressed and exploited, the slaves and the indentured, are unworthy of reparation, charity, welfare, even assistance, because providing such makes them “predators of their own species.”

Racial capitalists, historically in the United States, fiercely battled against all efforts and attempts of the oppressed to fight through the obstacles that maintained the white supremacy upon which racial capitalism is based. Wealth and power in the U.S. was originally and largely dependent on slavery, indentured servitude, and a clearly demarcated racial hierarchy. White America went to extreme and brutal lengths to enforce this hierarchy and by extension racial capitalism. White Americans in Tulsa, Oklahoma and Elaine, Arkansas murdered hundreds of free and successful Black Americans to ensure white supremacy. The echoes of these murders still reverberate today.

[. . .]

The massacres which occurred in Elaine and Tulsa in 1919 and 1921 were driven by a multitude of factors, but racial capitalism's socioeconomic framework created conditions within which such atrocities were possible, even likely. Black Wall Street's attempts to create a parallel economy and The Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America's creation of a union both threatened racial capitalism by showing that not only could the oppressed build and achieve great things without the oppressor's help, but also that the oppressed were capable not just of envisioning a better world, but of fighting for one.

By revisiting these events and considering them in their historical contexts, we are better able to see how vestiges of the past remain present in our political, social, cultural, academic, and legal institutions today. If we are to upend the social conditions which give rise to police killings of unarmed Black people and which gave rise to massacres and lynchings in the past, we must be willing to critique their source at the base of our society: racial capitalism. To do this, we must also be willing to ask, within the legal profession: how can we reckon with the role law, courts, and lawyers have played, and continue to play, in being paid to uphold, justify, and legalize systems of oppression. In the United States, early contracts were for slaves, early patents were for slave-restraining devices, early police forces were slave catchers, and early international law was crafted to ease slave-based commerce. These subjects should be taught and disseminated in a way which addresses and learns from these facts.

Associate Dean for Faculty Research & Development and Charles C. Baum Distinguished Professor of Law, Co-Director, Center for Racial Justice and Criminal Justice Reform, University of Arkansas at Little Rock William H. Bowen School of Law; J.D. Howard University School of Law (

University of Arkansas at Little Rock William H. Bowen School of Law, class of 2022.

Become a Patreon!