Abstract

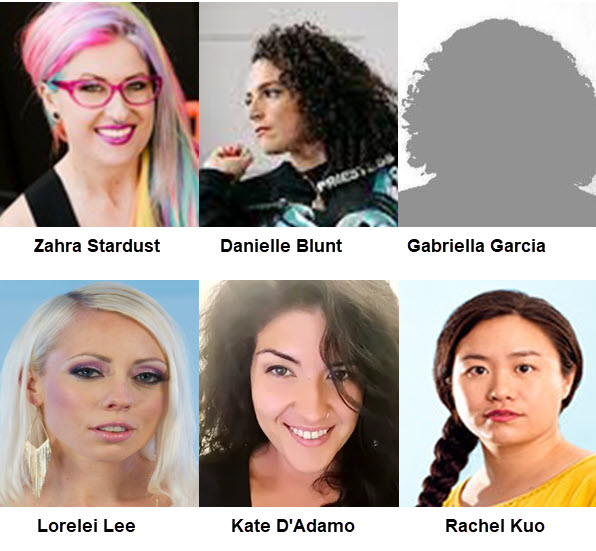

Excerpted From: Zahra Stardust, Danielle Blunt, Gabriella Garcia, Lorelei Lee, Kate D'Adamo and Rachel Kuo, High Risk Hustling: Payment Processors, Sexual Proxies, and Discrimination by Design, 26 CUNY Law Review 57 (Winter, 2023) (372 Footnotes) (Full Document)

On March 10, 2021, Danielle Blunt received a message that was, sadly, not unfamiliar to them. It read: ôYour business has been identified as presenting an elevated level of risk for customer disputes that we will be unable to support.ö The message came from the Risk Operations Team at Shopify only a few months after Blunt launched her new consulting business. Although Blunt was permitted to maintain the Shopify account, losing access to their ability to accept payments through Stripe effectively rendered their new website unusable.

On March 10, 2021, Danielle Blunt received a message that was, sadly, not unfamiliar to them. It read: ôYour business has been identified as presenting an elevated level of risk for customer disputes that we will be unable to support.ö The message came from the Risk Operations Team at Shopify only a few months after Blunt launched her new consulting business. Although Blunt was permitted to maintain the Shopify account, losing access to their ability to accept payments through Stripe effectively rendered their new website unusable.

As a chronically ill, immuno-compromised, in-person sex worker, Blunt had slowly transitioned to online sex work during the COVID-19 pandemic and decided to start a new business offering best-practice trainings for tech industry professionals. Having spent weeks building the new website and promoting their new business, Blunt had actively taken multiple security precautions so it would be harder to be traced back to their sex work persona. Despite this caution, Shopify's risk assessment team shuttered their ability to process payments.

Then, on March 24, Blunt received an email from another payment processor, Venmo, prompting them to ôconfirm your identityö and ôAct by April 10th to keep using your Venmo Balance.ö On May 15, they attempted to send funds to unbanked sex workers via a different provider, CashApp, for their recent contributions to a panel series Blunt had helped organize. Blunt was frozen from sending more funds via CashApp until they uploaded a photo of her identification and their social security number. Because the CashApp account was associated with their sex worker pseudonym, ôverifyingö their identity meant further connecting their legal and sex working identities in a way that would be permanent, traceable and place them at risk. As a result, over the course of three months, they effectively lost access to three different payment processors. This is not an unusual story, given that sex workers experience discrimination across multiple forms of online activity and political participation.

In this Article we examine the policies of banks and digital payment providers who refuse service to sex workers, sex industry businesses, and for other sexual purposes. We approach the umbrella category known as fintech using sex worker collective Hacking//Hustling's definition--financial technology that ôencompasses technologies and computer programs that either facilitate or disrupt banking and the movement of capital online .... Fintech includes crypto-currencies, crowdfunding, budgeting apps, and subscription services.ö This encourages us to think about these providers not only as facilitators for the transfer of money but as active gatekeepers, blockers, and obstacles to the equitable distribution of wealth. In their terms, we find broad definitions, blanket prohibitions, and reference to concepts of obscenity, harm, and legality--all of which are highly contested, geographically distinct and culturally specific. We assess the common justifications given by financial providers (including the policies of credit card companies, legal compliance, and unquantified assessments about risk). We identify the costs of financial discrimination for sex workers, including risks to safety, security, livelihood, and health. Finally, we point to a range of potential avenues for holding fintech into account--both legal (in the form of anti-discrimination re-visioning, decriminalization, destigmatization, and decarceration) and cultural (in moving towards public digital infrastructure).

In doing so, we advance an argument for why financial discrimination against sex workers is not an aberration, but rather is a specific manifestation of the current social, political, economic, and technological environment--namely the convergence of privatization, platform monopolies, and intermediary power with existing practices of stigma, discrimination, and exploitation. Existing discriminatory practices of assessing risk, creditworthiness, and lending are accelerated by the ubiquity of artificial intelligence. In addition, political pressure and increased legal liability ostensibly intended to pressure tech platforms into addressing criminalized activities including but not limited to fraud, money-laundering, terrorism, human trafficking, and distribution of child sexual abuse material has prompted a renewed push by those platforms towards verification, authentication, and risk detection. As a result, platforms have created policies that conflate sex with harm, illegality, and risk and deputize private actors, platforms, and individual users to do the work of police and the state.

Rather than simply arguing that sex work ought not be conflated with violence and/or harm, we seek to show how fears and panics around race, class, immigration, and sexuality create categories of criminalization and to build infrastructures of policing that in turn facilitate or require financial discrimination. This is not a respectability project to distinguish sex work from other forms of criminalized activity. The legal status of sex work should not be confused with whether the work is consensual or acceptable. Rather, we seek to problematize the political constructions of illegality and risk themselves. Addressing financial discrimination, therefore, requires not only increased transparency of and accountability for technologies of detection and surveillance, but a wholescale reassessment of the economic, regulatory, and social framework in which risk is understood, discrimination is framed, and the transfer of money is facilitated.

[. . .]

Despite the lack of academic consideration on this topic, financial discrimination against sex workers is of growing international media attention. As we have shown, the account closures, refusals of service, and seizing of funds should not be understood simply as glitches or aberrations in an otherwise fair system, one which could be incrementally improved through tweaks to various algorithms. Rather, they are part of a broader web of discrimination by design--a concept that has been used to explain how discriminatory decision-making impacts a range of social decisions, from the architecture of public space to the processes of machine learning. Financial discrimination stems from whorephobic laws, anti-sex policies, moral panic, and anti-migration agendas, which coalesce to form a regulatory agenda that criminalizes, stigmatises, and disadvantages people who exchange sexual services for money or trade. It thrives due to the tandem impacts of discriminatory human decision-making and its companion, algorithmic bias. When sex workers, and attributes imputed to them, are classified as ôhigh risk,ö whore stigma becomes encoded into automated decision-making tools, with poor or complicit human oversight. Such risk assessment software is driven by a regulatory environment that incentivises overcompliance and deputizes private actors to police its users whether or not the activity is criminalized. In effect, the denial of financial infrastructure increases vulnerability to exploitation and keeps sex workers constantly hustling to survive economic precarity and lack of formal protections. New sexual proxies operate to identify and algorithmically profile broad groups of people, including queer folk, activists, sex educators, sex tech businesses, and health promotion agencies. In this sense, financial discrimination is part of a larger, more comprehensive carceral system that maintains a gendered, classed, and racialized social order in which the labor of sex workers is undervalued and sex worker lives are treated as expendable.

As we see an increase in gendered criminalization (such as through the US Supreme Court's 2022 overturning of Roe v. Wade ), we are likely to see an increase of financial discrimination for those seeking access to reproductive health, abortion, and trans health care. While we have offered user accounts and experiences of financial discrimination to identify gaps in knowledge around how sex workers are being flagged, there is much more to be done. There is a need for further research into what internal decisions are made by platforms about how to detect risk, legality, or harm, and on what basis; what systems they use to identify sex workers and sex industry businesses, or to detect the sale of ôadultö novelties; what kind of sexual proxies they are using to pick up these users and transactions; how their algorithms are being trained, monitored and evaluated; and how this information is shared with state agencies or other third parties. At minimum, financial providers ought to make their algorithms and detection software publicly available so both researchers and sex workers can understand when, how, and why individuals have been flagged. They should release publicly available enforcement data on their patterns of refusals, forfeitures, and shutdowns so that the public can understand and evaluate how they are interpreting risk and actioning their policies. This includes data that compares the risks of each of these activities (chargebacks, fraud, trafficking) with other industries so that the public can determine whether sex workers are being treated exceptionally, disproportionately, or unfavorably, and so that financial providers can re-conceptualize risk and compliance.

This data transparency is necessary as one baseline strategy to hold fintech into account for both its automated and human decision-making, as well as to better understand how anti-discrimination law should address and respond to both algorithmic profiling and unconscious bias. Such data will be essential in unpacking how payment processors understand and operationalize their legal and policy compliance, which would assist policy and advocacy organizations in identifying problematic legal frameworks and lobbying for reform. It could also assist payment processors and banks in identifying how they can comply with the regulatory frameworks while still providing services to sex workers. Finally, more resources ought to be invested in supporting sex workers to challenge discriminatory laws and hold payment processors accountable. While there is promising movement in this space, attempts at accountability are restricted by both the lack of formal anti-discrimination protections for sex workers and the limitations of current anti-discrimination law in addressing algorithmic discrimination (and issues of exclusion more broadly). As such, these phenomena demand new ways of thinking about legality, risk, and discrimination that does not look to policing as a means of guaranteeing safety and inclusion. Finally, a key driver of this phenomenon is how sex work stigma has been baked into law and policy frameworks. Laws expanding categories of criminalization dually incentivize financial discrimination against sex workers and encourage discrimination-by-design under the guise of compliance. A core step in addressing financial discrimination and mitigating the harm must be the abolition of carceral systems of policing and punishment, which includes the decriminalization and destigmatization of all sex work and survival.

Zahra Stardust is affiliated with the Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society, Harvard Law School; Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence in Automated Decision-Making and Society, Queensland University of Technology; and Decoding Stigma.

Danielle Blunt is Co-founder of and Researcher with Hacking//Hustling sex worker collective and a Senior Civic Media Fellow at Annenberg Innovation Lab at University of Southern California.

Gabriella Garcia is Co-founder of Decoding Stigma, New York City, USA; Community Advisory Board member at Surveillance Technology Oversight Project; and Y9 Cohort Member at NEW INC.

Lorelei Lee is Co-founder of Disabled Sex Workers Collective, Founder of Bella Project for People in the Sex Trades at Cornell Law School Gender Justice Clinic, and a Researcher and Policy Analyst at Hacking//Hustling sex worker collective.

Kate D'Adamo is affiliated with Reframe Health and Justice, Maryland, USA.

Rachel Kuo is an Assistant Professor, Department of Media and Cinema Studies at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.