Become a Patreon!

Abstract

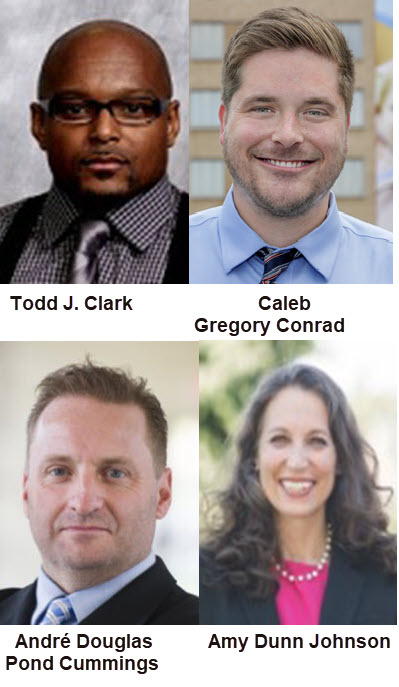

Excerpted From: Todd J. Clark, Caleb Gregory Conrad, André Douglas Pond Cummings, and Amy Dunn Johnson, Meek Mill's Trauma: Brutal Policing as an Adverse Childhood Experience, 33 Saint Thomas Law Review 158 (Spring, 2021) (203 Footnotes) (Full Document)

Meek Mill's life and career have been punctuated by trauma, from his childhood lived on the streets of Philadelphia, through his rise to fame and eventual arrival as one of hip hop's household names. In his 2018 track Trauma, Meek Mill describes, in revealing prose, just how the traumatic experiences he endured personally impacted and harmed him. He also embodies a role as narrator in describing the same traumas and harms that impact the daily lives of countless similarly situated young Black people in the United States. As a child, Mill's lived experience was one of pervasive poverty and fear, as the world surrounding him consisted of large-scale poverty, addiction, crime, violence, and death. As a young man--at just 19 years of age--he was beaten by police, wrongfully arrested and incarcerated, and ultimately convicted of crimes that he did not commit, becoming another statistic as a young Black man swallowed by the American criminal justice system. Meek's story, lyrics and contributions to hip hop illuminate the Black experience with law enforcement. His personal involvements provide a powerful narrative for exactly how a racially biased criminal justice system perpetrates a trauma that extends far greater than the law has traditionally recognized. This article highlights this narrative through the lens that Meek Mill provides because of his current prominence in hip hop and the importance of his narrative claims.

Meek Mill's life and career have been punctuated by trauma, from his childhood lived on the streets of Philadelphia, through his rise to fame and eventual arrival as one of hip hop's household names. In his 2018 track Trauma, Meek Mill describes, in revealing prose, just how the traumatic experiences he endured personally impacted and harmed him. He also embodies a role as narrator in describing the same traumas and harms that impact the daily lives of countless similarly situated young Black people in the United States. As a child, Mill's lived experience was one of pervasive poverty and fear, as the world surrounding him consisted of large-scale poverty, addiction, crime, violence, and death. As a young man--at just 19 years of age--he was beaten by police, wrongfully arrested and incarcerated, and ultimately convicted of crimes that he did not commit, becoming another statistic as a young Black man swallowed by the American criminal justice system. Meek's story, lyrics and contributions to hip hop illuminate the Black experience with law enforcement. His personal involvements provide a powerful narrative for exactly how a racially biased criminal justice system perpetrates a trauma that extends far greater than the law has traditionally recognized. This article highlights this narrative through the lens that Meek Mill provides because of his current prominence in hip hop and the importance of his narrative claims.

While no hip hop artist may ever impact the world to the same degree as Tupac Shakur, Meek Mill, in many respects, is the modern-day version of “Pac.” Mill's ability to tell a story in a way that evokes passion, energy and understanding is reminiscent of Tupac and for that reason, he is the perfect artist to narrate our legal proposition about expanding the way that the law conceptualizes and addresses “trauma.” Despite his success in achieving the status of a true hip hop icon, Meek Mill suffered the kind of childhood adversity and trauma that emerging health care research indicates leads to debilitating health outcomes in adulthood.

Powerful health studies conducted over the past two decades have uncovered the startling impact of Adverse Childhood Experiences (“ACEs”). ACEs are traumatic events that occur in childhood, ranging from abuse and neglect to other traumatic experiences derived from household and community dysfunction. Today, ACEs are generally placed by health researchers into seven to ten categories of childhood adversities ranging from sexual, physical and emotional abuse to the incarceration of a family member, living with someone who abuses alcohol or drugs and poverty, community violence and homelessness. These identified categories of trauma, although not fully understood or grasped as late as the 1990s, were known to occur in the lives of children all over the United States; however, the overall impact of childhood trauma on an individual's long-term health outcomes was only first measured in the now famous CDC-Kaiser Permanente ACE study. The findings of this study shook the health care world, forever altering the understanding of the link between childhood trauma and adult health outcomes. These links pushed researchers to look more deeply into the ultimate impact of traumatic childhood experiences on overall adult health. The groundbreaking study concluded that the more trauma a child experiences, the fewer years that child would live as an adult. In fact, in a 2009 study, CDC researchers determined that exposure to childhood trauma literally shortens an individual's lifespan. On average, a person with six or more ACEs died twenty years earlier than a person that had experienced no Adverse Childhood Experiences. reality, that traumatic childhood experiences are directly and inextricably linked to negative health outcomes, is now widely recognized in the public health and clinical literature. Dr. Robert Block, former President of the American Academy of Pediatrics, has warned that “[a]dverse childhood experiences are the single greatest unaddressed public health threat facing our nation today.” More recently, this literature has begun to explore the connection between trauma and race, outlining how structural violence and historical trauma--particularly violence and discrimination experienced by Black, indigenous, and persons of color--is often experienced both at the individual and community levels. Such work has focused on improving economic opportunities for trauma-stricken communities, improving the physical/built environment, and supporting the development of healthy social-cultural environments. The prevailing framework for addressing the ACEs crisis has been a medical model focused on interventions for individual survivors and communities rather than addressing the glaring systemic issues that directly contribute to the vast majority of the trauma suffered by those communities and the individuals and families that inhabit them. Largely and undeniably absent from the body of work on childhood trauma, and the proposed solutions to confronting and rectifying its deadly impact, is the exploration of how the American legal and justice systems, from municipal law enforcement to the appellate courts, stands at the epicenter of the current crisis. of the recognized categories of ACEs listed in medical screening instruments used by physicians to identity trauma have a direct nexus to the justice system. If we as a society are committed to treating ACEs as the public health crisis that they are, it is incumbent upon us to examine where and how our legal system is complicit in perpetuating trauma upon minority children. In addition, we need to consider how it can intervene--both at the individual and structural levels--to eliminate practices that contribute to multi-generational cycles of trauma and work to equip those with justice-system involvement to succeed and build the resilience necessary to heal minority individuals and communities who have been stricken by trauma and its life-long negative consequences. Indeed it is the responsibility of our justice system, as a major contributor to so-called “social determinants of health.” Mill, in his intimate autobiographical tracks of Trauma, Oodles O'Noodles Babies, and Otherside of America, describes experiencing not just several instances of childhood trauma as identified by the CDC-Kaiser Permanente study, but as a teenager, he suffered additional cruel trauma at the hands of U.S. police and a criminal justice system that wrongly imprisoned and unfairly positioned him in a revolving door between probation and prison. The data tells us that the trauma Meek experienced as a child and teenager statistically predicts a poorer life expectancy for him than those individuals that experienced no trauma or little trauma as a child and youth. Because of the anti-Black culture of policing in America, and because of the deep systemic racism that permeates the criminal justice system, simple exposure to U.S. policing and its courts should qualify as an Adverse Childhood Experience for Black and minority children--one that contributes to harmful adult outcomes, including a shortened life expectancy. Mill's personal childhood trauma as described in his music carefully extrapolates the ways that American policing and the criminal justice system literally traumatized and endangered his young Black life, as it does so many Black children.

This article begins in Section I by providing an in-depth examination of ACEs research, including how the groundbreaking original ACE study discovered the direct link between high ACE scores and poor health outcomes and the prevalence of ACEs in the Black community. It then turns, in Section II, to a brief discussion of the broad ACE category of social disadvantage, and how a child growing up in an environment built on a foundation of poverty and violence will inevitably have more trauma, more ACEs, and be harmed through his or her experience of toxic stress. Section III will provide an overview of anti-Black policing and how law enforcement, as currently constituted, traumatizes minority communities and youth. Section IV explains how criminal charging, jailing, and sentencing traditions have disproportionately targeted Black men, contributing to the trauma that their children and families experience with the loss of a loved one to death or incarceration. The article next argues that minority youth exposure to U.S. law enforcement agents and the justice system at large functions as an ACE for youth of color in a way that is simply not present for non-minority youth and, as such, should be added to the list of ACEs that are formally recognized by public health officials. Finally, the article concludes with how Meek Mill himself is seeking to reform a system rife with debilitating trauma. Throughout each section, Meek Mill, and the raw lyrics from some of his most personal tracks, will serve as an illustration, and example, of how social disadvantage, police misconduct and brutality, and the American criminal justice system at large, cause harmful and lifelong trauma for Black Americans.

[. . .]

Meek Mill's creative flow not only serves as a tool in advancing this article's argument that the law must newly consider traumatic experiences that Black children and families encounter with law enforcement and the criminal justice system as ACEs, but his current activism and initiative advances a compelling solution for addressing the concerns highlighted herein. Meek Mill's trauma, captured in creative art for the world to encounter, is merely a glimpse into the world that exists for minority children throughout the United States. Meek Mill's trauma, both experienced as a child raised in poverty and through wrongful arrest and imprisonment as a teenaged boy, is inexcusable. That his experience is still played out daily throughout the United States today is reprehensible. Surely the time has come to bring the necessary reforms to end childhood trauma, particularly that inflicted upon Black and minority children by U.S. law enforcement and the criminal justice system.

Todd J. Clark, Professor of Law, St. Thomas University College of Law; J.D., University of Pittsburgh School of Law.

Caleb Gregory Conrad, B.A. University of Arkansas; J.D. U.A. Little Rock William H. Bowen School of Law; Deputy Prosecuting Attorney, 11th-West Judicial District of Arkansas, serving Jefferson and Lincoln Counties

André Douglas Pond Cummings Associate Dean for Faculty Research and Development and Professor of Law, University of Arkansas at Little Rock William H. Bowen School of Law; J.D., Howard University School of Law.

Amy Dunn Johnson, Circuit Judge, 15th Division, 6th Judicial District of Arkansas, serving Pulaski and Perry Counties. B.A., Hendrix College; J.D., U.A. Little Rock William H. Bowen School of Law.

Become a Patreon!