Abstract

excerpted from: N. Douglas Wells, Thurgood Marshall and “Individual Self-realization” in First Amendment Jurisprudence, 61 Tennessee Law Review 237 (Fall, 1993) (376 Footnotes)(Full Document)

Thurgood Marshall's place in history as the first African-American to serve on the United States Supreme Court and his numerous contributions as Associate Justice warrant the attention that scholars have accorded his illustrious career. While Justice Marshall will be remembered for his opinions spanning numerous constitutional questions, his effort to imprint upon the consciousness of the nation his philosophy of the First Amendment has not yet received the recognition it deserves. A careful reading of Justice Marshall's writing reveals that he was a vigorous and principled proponent of the First Amendment.

Thurgood Marshall's place in history as the first African-American to serve on the United States Supreme Court and his numerous contributions as Associate Justice warrant the attention that scholars have accorded his illustrious career. While Justice Marshall will be remembered for his opinions spanning numerous constitutional questions, his effort to imprint upon the consciousness of the nation his philosophy of the First Amendment has not yet received the recognition it deserves. A careful reading of Justice Marshall's writing reveals that he was a vigorous and principled proponent of the First Amendment.

During Justice Marshall's twenty-four years on the Court he revealed himself as an ardent advocate of freedom of expression. During his tenure, his participation in First Amendment cases included forty-four majority opinions, thirty-five concurring opinions, and eighty-six dissents. His record in First Amendment cases led to his being described as one of the Court's most faithful protectors of individual freedom of expression. However, Justice Marshall's legacy will not be reflected in enduring precedents, embraced by a majority of the Court, for during his years on the Court he became increasingly isolated because of shifting political majorities on the Court and, also perhaps, because of the understanding of American life presented by his personal racial history. Nonetheless, Justice Marshall's First Amendment writings offer a unique jurisprudence, especially for those willing to read his candid dissenting opinions.

This Article examines Justice Marshall's First Amendment jurisprudence as reflected in his opinions and identifies those recurring themes of his philosophy that were central to his principled approach to resolving free speech issues. The Article begins with the premise that to uncritically attach the label “liberal” to Justice Marshall's First Amendment jurisprudence, without more searching inquiry, is to do an injustice to Justice Marshall's philosophy of freedom of expression. His record deserves more. As Professor Kalven has noted, the emergence of the civil rights movement by African-Americans had a significant impact on the development of civil liberties in this nation. Long before joining the Court, Justice Marshall was a central figure in that struggle; it does not follow that he would have lost his zest for the free speech issues which were so central to that movement once he became a member of the Court. Therefore, this Article has as its purpose an examination of the basic understandings upon which Justice Marshall relied in deciding free speech cases.

The thesis of this Article is that Thurgood Marshall's position in First Amendment cases reveals a coherent free speech theory: the value of speech in promoting individual self-realization in a democratic society ought to be the preeminent concern of the courts. This does not suggest that, in Justice Marshall's view, speech did not serve other societal values or that other values were not implicated in his First Amendment writings. However, this Article asserts that Justice Marshall implicitly established a hierarchy of First Amendment values and that individual self-realization, or self-fulfillment, was at the pinnacle of the hierarchy and that other values served by the First Amendment could be viewed as subservient or derivative.

I suggest that when there were competing values raised by the free speech claim or the government's claim in favor of regulation, Justice Marshall resolved the conflict by resort to an underlying scheme of values that honored the dignity and self-realization of the individual. Under this theory, he would give broadest protection to those forms of expression that advance the interests of the individual asserting the free speech right as a means of advancing both the development of personhood and a scoiety that honors the worth of individuals. Other free speech values, such as concern for striking a balance between stability and change, participation in democratic decision-making, and even attainment of truth, could consequently be viewed as secondary.

A review of Justice Marshall's decisions in First Amendment cases indicates that he most often tolerated government regulation of speech in cases where the speech involved relatively low individual self-realization value, even though the speech arguably advanced other free speech values, such as political decision-making. This stance alone would set him apart from the majority of the Court in recent years, since the Court has appeared to value speech relating to political debate more highly than speech serving any other values. Initially, it would seem absurd to suggest that Justice Marshall would sacrifice the truth-seeking or political decision-making values. These would seem to be of paramount importance to Justice Marshall, and this would appear to be borne out by his stance in freedom of association cases and press cases. However, I conclude that in his jurisprudence, these values could be subjugated to what I argue were Justice Marshall's greater concerns for “social justice,” which included advancing the dignity of the individual as well as assuring equality. Thus, where individual self-realization values were not implicated and the government regulation presented the greater opportunity for equality, as in Austin v. Michigan State Chamber of Commerce, Justice Marshall was able to find a governmental interest that outweighed the free speech claim.

In Justice Marshall's jurisprudence, concern for the dignity of the individual was paramount, and “individual” meant human being or groups of human beings and not legal constructs, such as corporations. Furthermore, his concern for other societal values served by free speech, such as participation in decision-making and accommodating social change, can be explained by resorting to Justice Marshall's judicial philosophy, legal training, and personal experience.

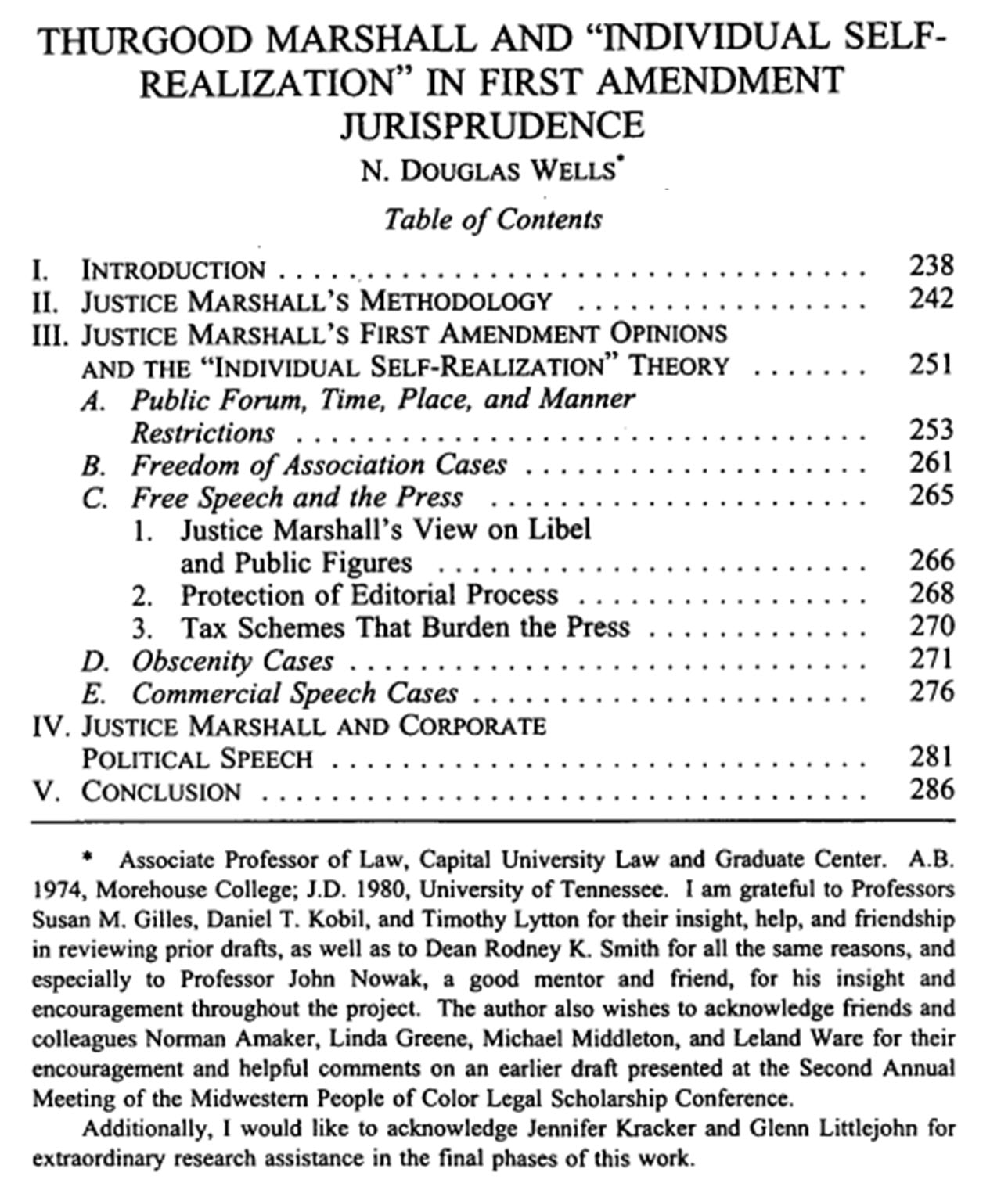

Part II of this Article addresses Justice Marshall's methodology in First Amendment cases and suggests some antecedents to the formation of his judicial philosophy.

Part III of this Article describes how Justice Marshall's opinions reflect the preeminence of individual self-realization. His opinions in public forum, freedom of association, freedom of press, commercial speech, and obscenity cases are the primary vehicles for this exploration.

Part IV demonstrates that Justice Marshall implicitly or explicitly accorded less value to attainment of truth and participation in self-governance values in free speech when individual self-realization values were not implicated. The primary vehicles for this discussion are Justice Marshall's opinions in cases raising the issue of political speech by corporations. Part IV concludes that Justice Marshall's First Amendment jurisprudence offered very broad protection to freedom of expression as a vehicle for assuring the dignity of the individual, including the politically and economically disenfranchised, and as a necessity for assuring the appropriate balance between stability and change in society.

. . .

Thurgood Marshall's judicial record reflects that as an Associate Justice he was a thoughtful, incisive, and above all else, principled jurist. His approach to First Amendment issues reveals a steadfast protector of freedom of expression. He adopted a principled approach to balancing First Amendment claims that allowed him to protect a broader range of speech and expressive conduct than did the absolutists.

Justice Marshall's performance in free speech cases indicates that he employed a coherent theory for resolving First Amendment claims and that that theory is best characterized by a recognition of individual self-realization as the preeminent value of freedom of expression. This led him to adopt a balancing approach, but he balanced with a “thumb on the scale,” in favor of expansive protection of free speech. The government could advance an interest that overcame the presumption in favor of the speech protection, but the government had to meet a very difficult burden. Justice Marshall's approach to First Amendment issues disfavored categorical approaches that value some forms of speech over others. Therefore, he accorded broad protection to speech in the public forum, political debate, and the press as well as to obscenity and commercial speech. The distinctions that he drew, consistent with the individual self-realization theory, were drawn between speech and conduct. In those cases where he was not bound by precedent, he permitted government regulation only where the government could show a compelling justification, which in the majority of cases meant that he had concluded that the asserted speech activity endangered the boundary between speech and conduct, threatening to become violent or disruptive action.

Finally, where free speech values conflicted, Justice Marshall resorted to a system of values that valued foremostly the preeminence of individual self-realization. When that value was not implicated, he would turn to other key concerns: balance between stability and change, equality of voices in the speech “marketplace,” participation in democracy, and attainment of truth.

Perhaps little of Thurgood Marshall's First Amendment philosophy will be seen in the evolving doctrine of the Court. Unfortunately, some of the promising lines of analysis offered by Justice Marshall have been abandoned by changing majorities on the Court. Nonetheless, in the area of freedom of expression, history will note--especially for those willing to read dissenting opinions-- that Justice Marshall stood firmly for the broadest protection of individual liberty. Justice Brennan has noted that dissents are often written for the day when the positions they advocate may command a majority and as a mechanism by which past or present Supreme Court Justices may have a “dynamic interaction . . . through dialogue across time with the future Court.” Hence, as new Justices are appointed to the Court, perhaps some will come to regard the paths urged by Justice Marshall's First Amendment jurisprudence as wise guidance.

Associate Professor of Law, Capital University Law and Graduate Center. A.B. 1974, Morehouse College; J.D. 1980, University of Tennessee.